Why I Put a Melee in a Romantic Novel

Share

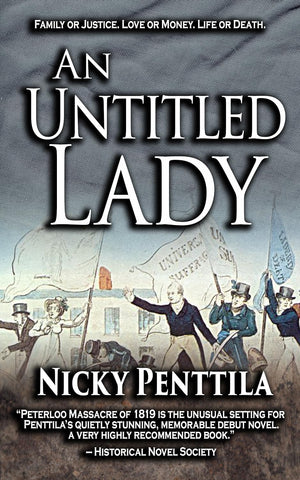

caption: Detail of an illustration by Richard Carlile of the Yeomanry attacking the meeting in St Peter’s Field, Manchester.

Why would a romance-loving writer like me set a story in the middle of a melee? My novel An Untitled Lady includes events around 16 August 1819 in Manchester, England, including a workers’ protest rally that ended with at least 15 people dead. It might seem odd to set a story about two people falling in love in the middle of that kind of trouble, but for me love helps people see things more clearly—including the outside world.

Romance is an adventurous, expansive genre: Romance readers absorb and accept new directions all the time. Vampires, zombies, Viking raiders, corporate raiders—we cheerfully read it all and more. Authors often include issues like post-traumatic stress, child abuse, addiction, bereavement and recovery.

We don’t shy away from social unrest and other mayhem: The shelves are filled with love stories that include unruly crowds and striking violence, starting in the nineteenth century with Shirley by Charlotte Brontë, North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell and even War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy. Gone with the Wind (1936) famously treats the Civil War, and both An Infamous Army by Georgette Heyer (1937) and Slightly Tempted (2003) by Mary Balogh include a retelling of the battles and aftermath of Waterloo. The melee in my book was dubbed “Peterloo,” a coinage based the rally’s location at St. Peter’s Field and Waterloo, that final, bloody battle of the recently ended Napoleonic wars.

It wasn’t that much of a stretch for me to think, “Why not Peterloo?”—although I did give it a pass on the first draft of the story. Something happened to me in 2009 that changed my mind.

Two things about me: I worked in newsrooms for more than two decades, and I now live just outside Washington, DC. From the first, I am confident that when I see or hear a news story, I can parse the language and know which are the pieces that are the news and which are the bloviating, link-baiting, and “needs confirmation” bits. From the second, I know that people protest in Washington every week, in numbers large and small, and for every reason—that’s what normal is, for DC.

In 2009, organizers connected to a group calling themselves the Tea Party announced they were coming to town. The news was full of it. Protests had been going on through the spring and summer in other towns, and organizers wanted to build that into a full-on protest event in the nation’s capital. A friend had seen a small one near Baltimore and said the rhetoric was high, as usual, but the emotion was higher. These people were on the way, they were red-faced angry, and at earlier protests some of them had brought guns.

Well. DC has plenty enough guns of its own; we sure didn’t need any more. Our town is home to a large number of people of color, and some of the words protesters and planners were using made me fear for their safety. Would there be guns going off in the Starbucks or the CVS around the corner from my office? Would there be guns going off on the Mall itself?

Each day in early September I read more worrisome news and speechifying about this next march. I was glad it was to be on a Saturday; I’d thought of maybe using a vacation day to stay home from work if it had been on a weekday. I checked with my friends to make sure their weekend plans didn’t include DC, something I had never done before.

And then the day came and— nothing. The march happened, an estimated 60-75,000 people showed up and made their dissatisfaction with the current political order known, and then went home. There were the usual skirmishes on the sidelines, never clear whether they were protest-driven or the usual peripheral shenanigans. It was just like every other big protest march. No guns.

I was gobsmacked. How could I have been so blind? Was I that prejudiced?

Apparently so. I went back to the news stories, and this time I found the same “might,” “could,” and “potentially” that resides in the text of every fear-inciting story about an event that hasn’t happened yet. I’d read the same words as always, but reached a different conclusion. And I’d acted on it, in my small way.

I did not like this new view of myself. I do not wish to be a person who could not see all sides. That day I’d been just an observer, but what if I had been in charge of DC security? Would the decisions I would have made then hurt or killed people?

Questions like those are how my story ideas start. I already knew about Peterloo from reading history, but I’d thought it too messy, too violent, to include in a love story. I’d read one romance novel that took place nearby, but it used only a second-hand report of the events to fuel a subplot.

Now, though, I had to use it, and because of its messiness. I had to tell a story that showed readers many different sides in a way they could not miss, which meant I first needed to see clearly many, many points of view.

I had a lot of help, in terms of research. Reporters were on the ground during the march, unusual at that time. They and other eyewitnesses wrote soon after for papers, pamphlets, and later for books. Records are available online from trials and civil proceedings that arose from the event.

Like today, their reports diverge from one another to a bewildering degree. In 2009 in DC, scribes reported the number of marchers as 60,000, 75,000, 1 million, even 1.2 million; most finally settled on 60–75,000. In 1819 in Manchester, estimates also varied, from 30,000 to 150,000, and also finally settled on 60–80,000—an astonishing figure at a time that lacked cell phones and the Internet, autobuses, or Porta Potties. And even now, reasonable people disagree on who was where on St. Peter’s Field, who slashed whom, and whether the slayings should rightly be called the Peterloo Massacre or the Battle of Peterloo.

In my story, we see through the eyes of manufactory owners and the weavers they are putting out of business, of lords and their tenants, and of one warehouse owner and a woman of unknown provenance. I set my couple right at the axis of the debate, trying to bridge the gaps between the classes. How better to explore the intimacies, the intricacies of our world than through stories of family?

For a romantic historical novel, it was perfect.